Someone Tells You Not to “Walk Like a Victim”?

When I started teaching self-defense more than 20 years ago, I was told about a study that supposedly explained how attackers choose their victims. Video tapes of people walking down a crowded street in New York City were shown to men who were in prison for violent crimes, those men were asked who they would attack, and they all chose the same people.

The person who told me about this study had much more teaching experience than I did, but he didn’t give me enough information to make a good decision about how meaningful the research was. Information like how many people were studied, whether the research was outdated, or how the vague concept of “likely victim” was defined.

A lot of what we know about violence and safety is complicated and nuanced, but a lot of safety advice is not. So many of our students have gotten advice that is simplistic to the point of not being helpful: don’t go out alone at night, don’t read a map on a street, don’t park next to a van. Some of these strategies make sense in specific circumstances, but as blanket rules, they are more likely to stoke fear, racism, and stigma than actually help us discern whether we are at risk. Also, most of our students are part of communities that are much more likely to be harmed by someone they know, so safety advice that is only relevant to strangers can be unhelpful. Or worse, it can direct their awareness away from situations that are truly unsafe.

A few weeks ago, I finally found this study, which has inspired decades of oversimplified statements about why we should not walk like victims, including some relatively recent blog posts. It’s called “Attracting Assault: Victims’ Nonverbal Cues.” It was conducted by communications professor Betty Grayson and psychologist Morris I. Stein and it was published in 1981, so it’s more than 40 years old.

In the first part of the study, Grayson and Stein asked 12 men who were in prison for assaults against strangers to watch video footage of people walking in an area of New York City that was thought to be high crime. These 12 men watched videos and rated people based on how easy they would be to assault. Researchers then turned the men’s opinions of these pedestrians into a 10-point scale. They then asked 53 other incarcerated men to rate the walkers based on that scale. It’s worth noting that the 87% of the men in the study were Black at a time when, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, only 41% of the U.S. prison population was Black.

This second group of 53 incarcerated men used the 10-point scale to rate the pedestrians in terms of how easy or hard they would be to attack. Videos were then divided into 2 groups – those that got the highest rating from more than half the participants were put into one group (“victims”) and those that got lower ratings were put into the other (“non-victims”). From there, Grayson and Stein hired some people who were experts in analyzing body movements to identify differences in the walking styles of the “victims” and “non-victims.” Based on the movement analysis, Grayson and Stein made observations about the types of walks that made people appear more vulnerable.

It’s worth noting that the group of 53 incarcerated men was not uniform in how they rated the videotaped pedestrians. The range of agreement was from 27 (about half) to 36 out of 53. Second, the common characteristic among the people who got the highest rating on the “likely victim” scale was that they were older women. Twice as many older women were included in the “victim” group as any other age and gender. Then, once the groups were assigned, older men scored highest on the easy victim scale. The reality that people’s chances of experiencing violence have more to do with their demographic characteristics than anything else is not new. But it’s telling that this was an outcome of a study that sought to demonstrate that people’s individual behavior attracts crime.

The body mechanics experts identified 21 categories of movement, but only 5 had statistically significant differences between the people previously classified as victims and non-victims. And even when statistical tests found significant differences, the movements of the pedestrians in the two groups were not uniform. One example is the length of people’s stride. Those rated as “non-victims” all had a medium stride, meaning that the steps they took were neither too small or too large for their height. But half the group classified as “victims” also had medium strides. “Among the 14 victims,” Grayson and Stein wrote, “8 had medium strides and 6 had long strides. Among the non-victims, 15 had medium strides and one had a combination stride that was not classifiable.”

Other movement differences included how people shifted their weight, whether they swung their arms when they walked, and if they swung or lifted their feet. While statistical tests showed differences in all these areas, about half of the people classified as “victims” moved in the same ways as the people classified as “non-victims.”

What do I want to take away from this study? First of all, there is nothing wrong with walking with purpose or moving through the world in a way that projects confidence. Moving in a way that makes us feel calm, grounded and powerful can be beneficial. There are areas of movement education and dance therapy that study the way people move in meaningful ways and a lot of people have found that different types of movement training help them heal from trauma.

But getting carried away with our stride length or how we swing our arms can create unnecessary stress. Or worse, it can lead to victim blame. Nobody deserves to be assaulted no matter how long or short their stride is or how they swing their arms. Putting too much emphasis on this kind of detail can divert us from our real work – analyzing the conditions that make violence and abuse possible and changing those conditions, both in the moment and in the long term.

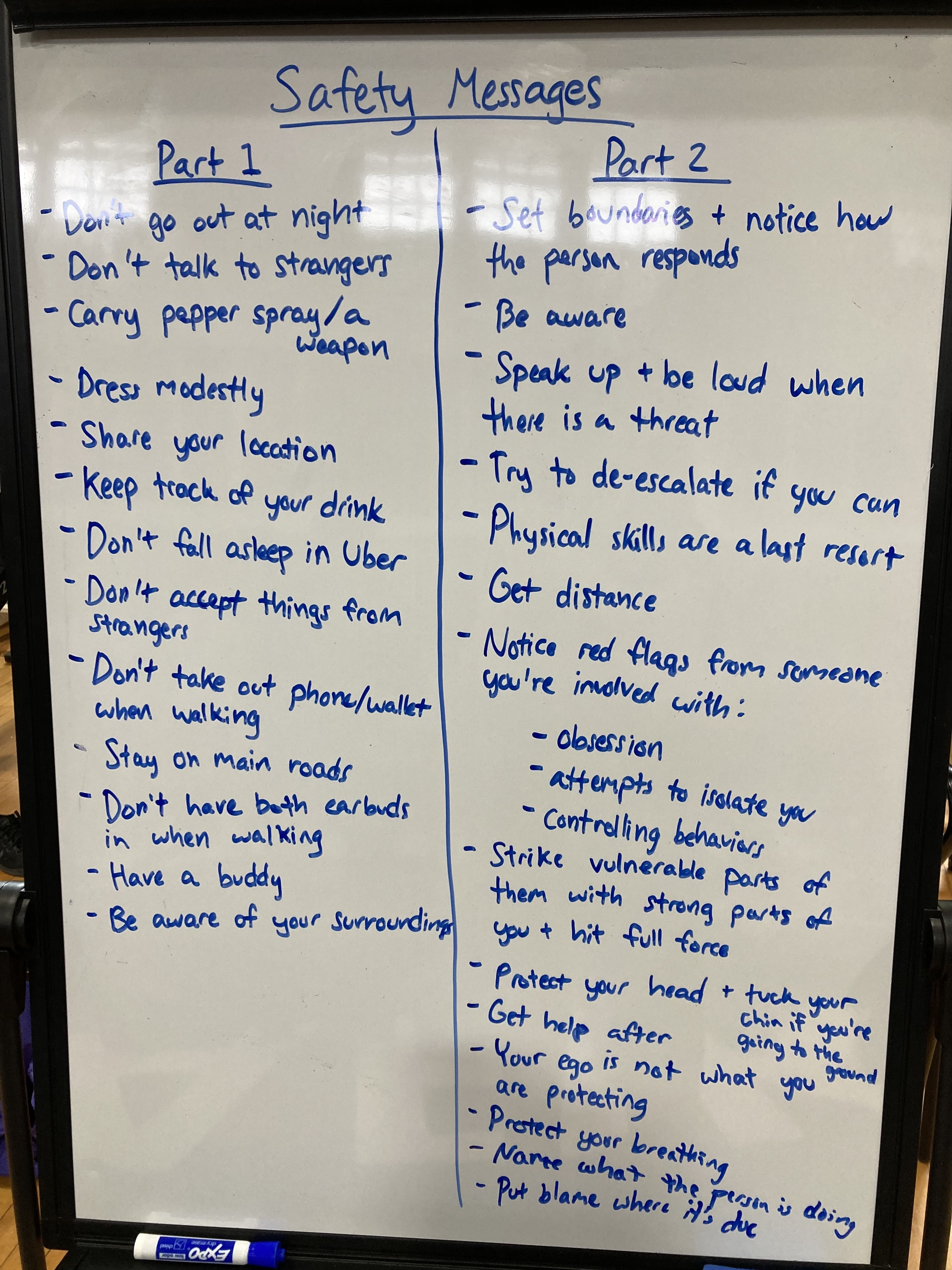

On the first day of some of our teen classes, we ask students to tell us the safety messages they’ve heard and whether those messages make them feel more or less powerful. Too often they tell us about messages that make them feel more fearful and that direct them to make their lives smaller. On the last day, we ask students what safety messages they would give others. If we’ve done our job, the list students make on the last day will be a stark contrast from the first – all about living bigger, bolder lives, speaking up, and making choices that work for them.

Meg Stone

(Alt text: Whiteboard with safety messages separated into two columns: those that make participants feel fearful, and those that made them feel empowered.)